Breed of the Border

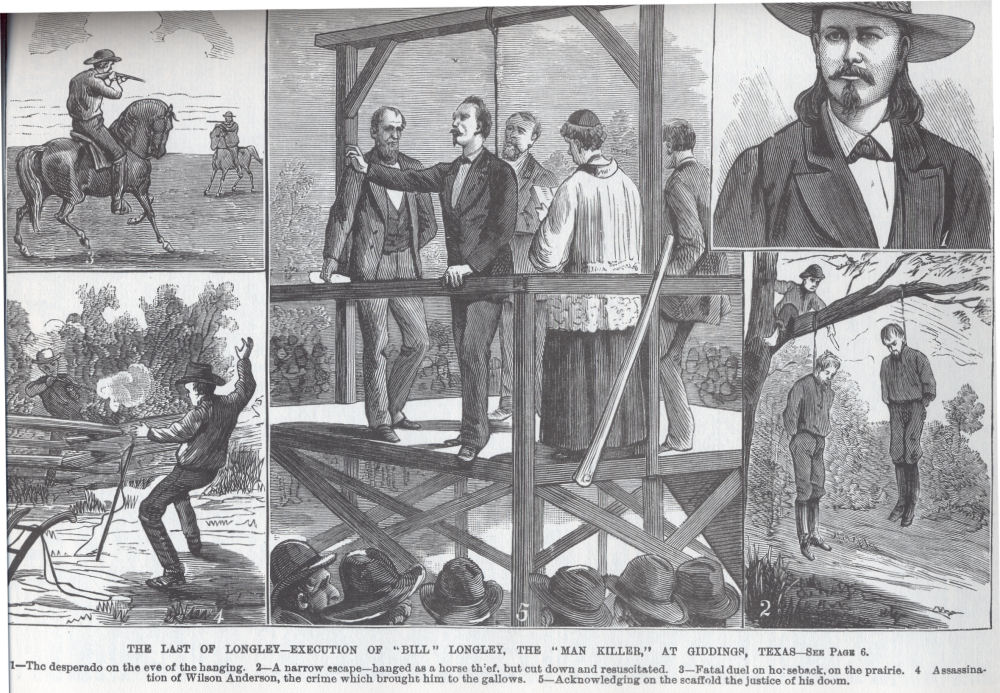

BILL LONGLEY

He was a man before he was done being

a boy. That was at once Bill Longley's fate and the explanation

of this "big old He" of the long line of Texas gunmen,

for -- even more than Cullen Baker -- Longley was Number One

of the modern gunslingers.

He was a child of the Texas frontier.

Upon him environment cut like a lathe-tool. Born October 6, 1851,

on Mill Creek in Austin County, at the age of two he was taken

by that God-fearing veteran of Houston's army, Campbell Longley

his father, to Old Evergreen in Washington (now Lee) County.

He was ten when the Civil War got fully

underway. Old enough to understand the bitter feeling between

the two factions which, in Lee County as elsewhere in Texas,

were local typifications of the North and the South. Old enough

to understand the fury of the secessionists when Campbell Longley

voted the Union ticket, a rage checked before it reached the

stage of killing only by the San Jacinto record of young Bill's

quiet, determined father.

Bill Longley was always large for his

age. Six feet tall from his fifteenth year, his weight at maturity

was to be two hundred pounds so magnificently proportioned as

to make him look slender. He was the idol of the boys at Evergreen's

field schoolhouse. Dark-eyed, dark-haired, his Indian-like face

could smile or lower in the same minute. He rode like a Comanche.

He could not remember when the "hogleg" shaped butt

of the Colt's pistol was not familiar to his hard big palm.

Behind him was the background of the Texas

pioneer who had asked no odds of anything thtg ran or walked

or crept or flew. The Texan of incredible deeds, of the Alamo,

of San Jacinto. This young gamecock being bred by quiet old Campbell

Longley had in him the fiery independence of habit in thought

and action which made the Texan of the '30s onward an adventurer,

a hell-for-leather fighting an, whose suyperior has never been

seen.

He was raw material at fourteen, but destined

to be graved into what he became without much more delay, for

the South's second war began with ending of its first, a savage

guerilla war, fought never on a formal battlefield, but in a

thousand desparate, bloody skirmishes, marked by bloody cruelty

on both sides.

In Evergreen, the tiny community flanking

the Austin-Brenham road, Bill Longley was a leading spirit among

the younger generation. His size, his courage, his amazing skill

with twin Colts, a certain fierce elan which was never to desert

him, made him a marked figure among the gatherings at the crossroads

blacksmith shop and store, under the wide shade of the court

house oak -- which had served both as justice court and gallows,

in its day, and which still stands a brooding gint over that

quiet land.

The carpetbagger and the negroes were

the problems discussed at these gatherings of the disfranchised

whites. The older negroes were giving no trouble. But the younger

freed men were drunk with liberty and license. Incited to swaggering

insolence by the riffraff whites in power, protected by troops

against prosecution for any crime, they were intolerable to the

intensely proud people who were being stupidly affronted by the

worst element among their conquerors.

When a week's tale of outrages major and

minor was told, with the sullenly hopeless reflection added,

that no legal process, no orderly method, of recourse was available

to the outraged, then the human, the natural, reaction among

a people of unbroken iron temper was the impulse to hit back.

The stage was set. Bill Longley, standing

under the court house oak, with unwavering dark stare going from

one face to another, was in the grip of shaping events which

-- he proved later by his letters, he understood not at all.

All he knew was that conditions were such that no white man of

any pride of race or history could endure them. He was no philosopher,

no thinker. His brain was director of that magnificent body of

his, no tool for abstract thought.

Bill Longley . . . There are old men yet

alive who squint across the mists of a long half-century and

see him as he was in his heyday. Hunkering in the sun with back

to some corral, they mutter his name in their beards and recount

the Longley legends. He rides again, gigantic on phantom caballo,

across the blue-bonneted prairie, smoke wreathing from the muzzles

of his Colts, the elfin echo of his fierce yell carrying to us,

as once it carried thunderously into the cabins of the negroes

and sent them cowering and mumbling to the shadowed corners.

. .

He belongs to Texan folklore . . . he

stands at the head of a long procession of Texas gunmen, slingers

of the sixes who were to set style and pace for the Genus Gunfighter

elsewhere on the frontier that stretched from Montana to Mexico,

from Mississipi to California.

He is the major figure of the beginning

of the Gunman Cycle that roughly embraced the span of years between

1860 and 1900, the period in which amazing skill in the mechanics

of pistol-handling was developed, when gunplay became a be-all,

end-all, an art separate from the business of mere promiscuous

killing.

A LOUD-VOICED negro sat his norse on the

Camino Real, the ancient Royal Highway of the Spanish, which

ran from Bastrop to Nacogdoches. He was cursing certain white

men of the Evergreen neighborhood. Beyond him Bill Longley lounged

in his saddle, hands held loosely on the great horn, listening.

"And Campbell Longley," the

negro took up another name.

He cursed Bill Longley's father, but only

for a sentence. The huge sixteen-yeazr-old had moved. Down to

the curving butts of the Colts sagging at his thighs his hands

flashed. The negro saw and loud in the silence his hands slapped

the stock of the rifle across his lap.

"Don't you move that gun!" Bill

Longley snarled at him.

But the rifle lifted. Bill Longley spurred

his horse and it leaped forward, turned sideway with knee-pressure

and slight body-swaying of its rider. The rifle whanged! but

the whirling horse had carried Bill Longley clear. Back it spun

and as it straightened out into a gallop, Longley fired. The

negro came sideway, sliding out of the saddle with a bullet hole

through his head.

Sure that no second shot was needed, Bill

Longley pushed the Colts back into their holsters. He took down

the lariat from his saddle and shook out a loop. He tossed it

deftly, to encircle the dead man's neck. He dragged the body

off the road and to a shallow ditch. He buried it . . .

In the first reward that Governor James

Coke posted for Anderson's murder, Bill and James Longley were

included, but James was not in the second one. Bill wrote to

a friend that his brother James had nothing to do with the murder

of Wils Anderson.

|

Reinterment of Bill Longley, 19 July 2001

Reinterment of Bill Longley, 19 July 2001