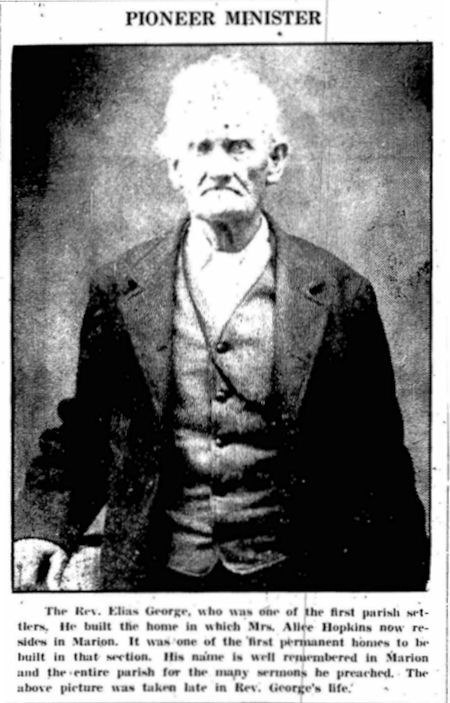

I was born on a farm near Hamburg,

Perry County, Alabama, in 1842. Elias George and mother, Ann

Bass George, were the parents of nine children -- four sons and

five daughters, of whom I was third from the youngest. All lived

to maturity, married and raised families, except one brother,

"Jeffy," two years my senior, who at the age of eight

years was thrown from a runaway horse.

My parents were missionary

Baptists, and we were early taught to reverence the name of Jesus,

respect the Sabbath day, be kind and charitable to the poor,

to servants, and to animals. There was family worship every night

before retiring, and my mother would have the servants come in

and to join us at such times. We were a happy family because

children and servants were taught obedience to those who ruled

them. We loved our servants and they loved us.

My father, being a slaveholder,

had a large plantation on which many supplies for home consumption

were raised, such as corn, cotton, potatoes, barley, and peas.

The home was a large, rambling two-storied building, and each

of the various rooms had a fireplace. But the room that charmed

me most was the nursery -- a large room with windows facing southward,

overlooking the pasture, and in the springtime there was much

interest in the horses and the little lambs as they chased each

other and gamboled in the field.

Our black mammy Chloe, was

installed as guardian and caretaker of the nursery. Its inmates

included three children, from one to five years old and two nurse

girls, Mariah and Harriet, who were ten and eleven years old.

The girls, under the supervision of mammy Chloe, would see to

our bathing, dressing, and feeding. When the weather permitted,

we were kept out doors in the sunshine and although the girls

ran and played with us, our black mammy was ever near and watchful

that no harm befell us.

It is difficult to make it

understood what love we had for Mammy and the girls. This attachment

lasted even to old age. Mammy died just a few years .. (original

sheet cut off).

I would not have one think that our precious mother neglected

her little children under these conditions and surroundings.

She had duties devolving upon her, which could not be done by

others. There were nine children to clothe and feed. While she

had servants who cooked, washed, ironed and sewed, she supervised

each department. There were no sewing machines nor ready-made

clothing. We were strangers to most of the conveniences in common

use today. Even soap and candles were made at the plantation.

My father raised everything possible at home and a yearly trip

to New Orleans resulted in the equivalent of a carload of provisions,

dress goods from England or New England and many other things

needed for the plantation. Oranges, apples, dried fruits, and

candy were bought by the barrel.

How well do I remember the

picturesque surroundings of our home. There was a long sloping

hill to the rear of the house, at the foot of which was a cold,

gushing spring, and directed channels went forth to the house

lot, chicken yard, and other needed places. A milk house was

built over this spring, the floor of which was laid of large,

flat rocks, so arranged that the stream was conducted over a

channel two or three inches lower than the floor and wide enough

to hold several pans of milk and butter. Our home was surrounded

with mockingbirds, swamp sparrows, field larks, whip-poor-wills,

blue jays, and cardinals. They were never disturbed and consequently,

many became quite tame, often feeding with the chickens, geese,

ducks, turkeys, and peafowls. The whip-poor-wills could be heard

at night in the swamp below, sometimes coming into the garden

as though they wanted to serenade us from the branch of an oak

tree near the house. I recall an evening twilight when one ventured

on the lawn near the house-steps and called lustily "Whip-poor-will!

Whip-poor-will!" and after satisfying himself, he flew to

his companions in the swamp and soon the air was filled with

their "Whip-poor-will! and "whip-will, the widow!"

Their concert lasted through the night, interrupted occasionally

by the deep, sonorous voice of an owl loudly calling, "WHO!

WHO! WHO! WHO! WHO! ARE YOU!" The loud laugh of another

owl answered, "WAH! WAH! WAH!"

. . . It is needless to say

that the dear old home where my mother and father had lived since

their marriage and which had been the birthplace of their nine

children, was doomed. Also, a beautiful new home near Marion,

Alabama, was being completed. This was a large, two-story house,

quite modern in all its appointments (for that time). The inside

work was superior to anything of its kind today; the plastering

was very hard and glazed. The parlor and hall were heavily frescoed

around the edges of the ceiling, with a large wreath of flowers

in the center of each for the chandeliers. My older sisters and

brothers were at the age when they needed to be in college, as

they had outgrown the country school. To educate them had been

the incentive for building in Marion, as it was a residential

city of schools and churches.

But to my father, nothing was

too great a sacrifice for [Louisiana] this "Land of Paradise"

-- not even the many friends and relatives with their earnest

protests, or his popularity as a minister of the gospel. Nothing

could outweigh his desire to possess a home in this unexplored

wilderness---a venture of toil, self-denial, hardships, and untried

experiences. Without taking it to the Lord in prayer, and seeking

divine guidance of Him whom he served, he straightway sold his

valuable plantation and lovely new home at a sacrifice, and was

soon in readiness for the journey by caravan. Early in the spring

of 1848, the day for departure arrived. Three or four families

decided to cast their lot with us in going west, which at that

time was as far distant as is California now. The trip had to

be made in private conveyances, drawn by horses and mules, and

it would take weeks to reach our destination. Besides this, my

father was taking with him 400 Durham cattle which were to be

driven by herdsmen.

The caravan included about

50 covered wagons, carriages, carry-alls, and buggies. These

and the horseback riders assembled at our home, and many friends

came to bid us "un bon voyage". How well do I remember

that first day, which to me seemed a gala affair with many more

to follow. I was too young (six years) to realize what it meant

to those on whom the burden fell, nor what awaited us in the

future. The morning was bright and beautiful, and although the

sun gladdened the earth, it was unable to penetrate the gloom

which hung like a pall of dark foreboding in the hearts of some

who reluctantly bade a last farewell to loved ones.

My mother rode in a carriage

with four of her young children; a brother older and a sister

and brother younger than I. The driver's seat was high in front,

and in the style of the period, the nurse's seat was in the rear.

This was supplied with a step or foot rest and arms, as with

an armchair. The first day being cold and crisp, mother had the

driver stop at a store as we passed through Greensborough, and

bought us children beautiful wool hoods and each a tin cup, painted

red and blue, with "Boy" or "Girl" stamped

on it. These were suspended from our necks with ribbons.

The caravan necessarily traveled

slowly and when we children were tired of riding, mother would

let us get out and walk, always attended by the nurse . . . Long

before night, the captain (father) always went ahead to find

and arrange for a suitable camp ground where wood and water could

be obtained, for provisions also to be made for the cattle as

well as the teams of mules and horses. Having found such a place,

he would wait for the crowd.

The camp ground reached, the

overseer of the negroes superintended the location of wagons,

tents, and animals. The negroes' tents were grouped by themselves

and the white families were in a different location. Each family

of negroes had its separate tent; each woman cooking for her

own family, while the men got the wood, attended to the feeding

and caring for the stock and pitched the tents. There were log

fires in front of family tents, and after all were fed and the

little children were in bed, the white families would visit each

other,---sit around and exchange experiences and jokes till nine

or ten o'clock. The negroes would have their social time until

the gong sounded for retiring; after which quiet soon reigned,

except for the occasional lowing or neighing of an animal. At

five o'clock, the gong again sounded and all were up and hustling

with preparations to travel. Then at noon, a stop for a couple

of hours was made, with rest and lunch for man and beast.

We had to cross the Tombigbee

River in Alabama which we found to be a half-mile wide from recent

rains. It took two or three days to make the crossing, for the

cattle had to be ferried across. Upon taking one load, the cattle

became frightened and stampeded, and several leaped from the

flat-boat and were carried by the swift current down stream,

and two or three of these were never recovered.

Having surmounted this obstacle,

we proceeded on our journey with nothing of importance to note

except that one night we camped in a lovely grove of oak trees

enclosed with a rail or worm fence. A railroad track ran along

the outside of this enclosure, and we were warned not to cross

the fence; that a train would pass by very soon. We hadn't waited

long when a shrill whistle heralded its approach. We all stopped

and gazed at the wonderful monster, as it seemed to me, for in

those days, railroads were rare to country people.

At last we reached the Mississippi,

which we crossed at Vicksburg on a ferry . . . We finally reached

our destination which was a beautiful grove of oak trees, in

the midst of which was an eight-roomed cottage. Also, there was

a summer-house covered with coral honeysuckle and woodbine and

in the yard there was an abundance of flowers.

My father had purchased this

farm with 600 acres of improved land and under cultivation, to

serve as a temporary home until there were further developments.

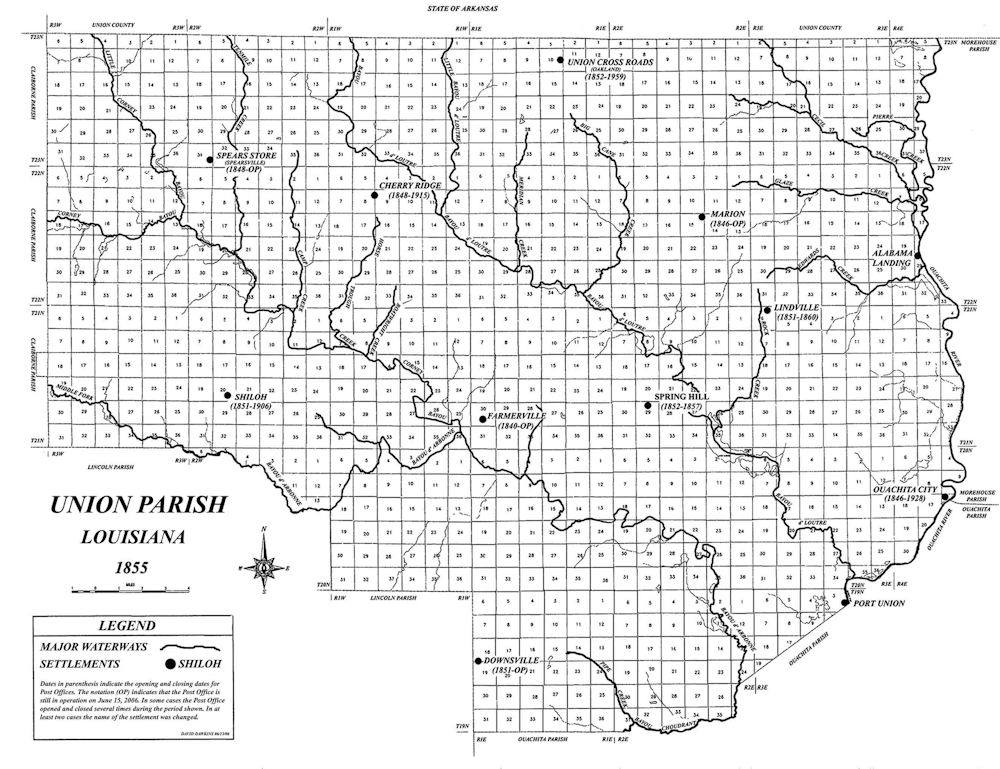

This home was three miles from Marion, a village in north Louisiana,

in Union Parish. It was settled and named for Marion, Alabama

by its earliest settlers who had come from that place. Father

had bought 4,000 acres of timbered land within four miles of

Marion, which was to be cleared and converted into a plantation

-- with cottages for the negroes, a dwelling for the overseer,

and with gardens and outhouses. This kept all hands busy for

the first year, with only time enough to cultivate the 600 acres

of the home place. [There

was a virulent fever epidemic and her mother, Ann Bass George]

. . . had been for the last time to see her sick servants.

She found the maid dead and the cook in a dying condition. Mother

prayed with her and comforted her as best she could. Upon leaving,

Julia put her arms around mother's neck and said, "Miss

Ann, meet me in heaven".

The next day mother was not

feeling well, but did not go to bed. That night, she had a congestive

chill, and at four a.m., she went to meet Julia in heaven. Her

death was so sudden and unexpected, that father was beside himself

with grief and for several months the physicians were afraid

he would lose his mind.

We three children were now

wholly dependant on relatives, friends and servants. Although

mother died in a room across the hall from where we were, we

knew nothing of her death till three weeks later. The first thing

that seemed to call me back to consciousness was brother Elias

crying and begging for mother. Father was holding him on his

lap and when he continued to plead, father burst into tears and

told him mother had gone to be with God in heaven . . .

After the death of my mother,

father seemed so disconsolate and broken I spirit, that his friends

and older children encouraged him to find a companion for himself

and a mother for his children. He finally wrote to Mrs. Ross,

a very excellent lady of character, culture, and refinement,

reared and educated in Richmond, Virginia and who was then living

on a plantation that adjoined our former home in Alabama. This

lady and her sister, Sarah and Mary, were both widows; Mr. Bryant,

husband of Mary, had died soon after moving to Alabama, and Mr.

Ross, Sarah's husband, died not long after we came to Louisiana.

It was satisfactorily arranged

between my father and Mrs. Ross, and the following spring (1852),

father went back to Alabama and they were married. It took two

or three months to arrange her affairs and get all things in

order for the moving to Louisiana. As the sisters would not be

separated, transportation for the two families had to be made

and each had many slaves and several children. It was a big responsibility

but it effectuality diverted father's mind from his own personal

grief.

Finally, the second caravan

left the same neighborhood for Louisiana, similar to the first

which had gone four years before, with many vehicles and covered

wagons. All arrangements for homes and land had been made previously

and were awaiting their arrival.

One afternoon, when Sue, Jane,

and I were attending school, a handsome youth, about 18 years

old, came into the classroom and asked for the George sisters,---introducing

himself as Jim Ross, our stepbrother. On looking out of the window,

we were surprised to find the street lined with carriages, buggies,

wagons, and horses. The young people had come in advance of the

wagons, while my father's wife and her sister were in a carriage

to the rear. My father was on horseback and there were several

others . . .

Our teacher excused us and

we went out to meet our new relatives who insisted that we go

home with them, which we were only too delighted to do. We didn't

even ask permission of our aunt, with whom we were boarding,

but sent word where we were.

Father was so busy seeing that

the negroes were settled, that he did not know until that night

that we had come home with the crowd. When he finally came into

the house, three eager girls unexpectedly threw their arms around

him. Imagine our amazement when he did not respond, but seemed

dismayed at our presence. He said that we must return to school

early in the morning, because there was cholera among the negroes,

contracted while passing through the Mississippi swamps. A negro

woman had died of it that night just as the wagon in which she

rode, stopped at the gate. The next morning before breakfast,

a girl 12 years old, came in and said she was sick. Father examined

her and gave her the cholera remedy, but at noon she was dead.

The place was immediately quarantined. In two weeks 16 negroes

had succumbed.

|